Read a version of this story in Arabic.

Story highlights

Egypt's raging conflict "may lead to the collapse of the state," defense minister says

The remark is a warning that things are getting out of control, analysts say

But experts largely agree that the remark is "a bit over the top"

Egypt's government needs to build "confidence" among its people, Clinton says

The renewed bloodshed and defiant protests in Egypt prompts a provocative question: Could Egypt really collapse?

Just two years into a revolution that ignited during the Arab Spring, Egypt’s defense minister warned this week the raging conflict “may lead to the collapse of the state and threaten the future of our coming generations.”

READ: Egyptian secular, Islamist groups meet to try to end conflict

On Wednesday, analysts described that statement as overreaching, but none dismissed the severity of the country’s problems.

“His comments were a bit over the top,” said Joshua Stacher, a fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center of Scholars.

“It depends on what your definition of what ‘collapse’ is,” added Steven A. Cook, senior fellow for Middle Eastern studies at the Council on Foreign Relations. “The economy is certainly in terrible shape.”

James Coyle, director of global education at Chapman University in California, said the comment by Defense Minister Gen. Abdul Fattah al-Sisi was “a bit of an overreaction.”

READ: Official warns of Egypt’s collapse as protesters defy curfew order

“But five days of riots and tens of deaths and thousands of demonstrators still in Tahrir Square two years after the fall of (Hosni) Mubarak, I can understand why he would say it.”

Analysts agreed that the remarks should serve as an alarm.

“It was a warning to everybody – the opposition, the Brotherhood – that they’ve got to get their act together,” said CNN correspondent Ben Wedeman in Cairo. He was referring to the Muslim Brotherhood, the Islamist party to which President Mohamed Morsy belongs.

READ: Demonstrators ignore curfew in restive Egyptian city

The military – the powerful bulwark for Egyptian secularism that temporarily governed the country after the revolution ousted longtime ruler Mubarak – is worried about civil war.

“This is a telegraphed message to everybody that this is getting out of control,” Wedeman said.

U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton also addressed the defense minister’s warning of a collapse.

“I hope not,” she told CNN Tuesday. “That would lead to incredible chaos and violence on a scale that would be devastating for Egypt and the region.”

READ: Clinton warns Egypt collapse would devastate the region

Morsy’s government needs to understand that the revolution’s aspirations “have to be taken seriously” and that “the rule of law applied to everyone,” she said.

“It’s very difficult going from a closed regime – essentially one-man rule – to a democracy that is trying to be born and learn to walk,” Clinton explained. “I think the messages and the actions coming from the leadership have to be changed in order to give people confidence that they are on the right path to the kind of future they seek.”

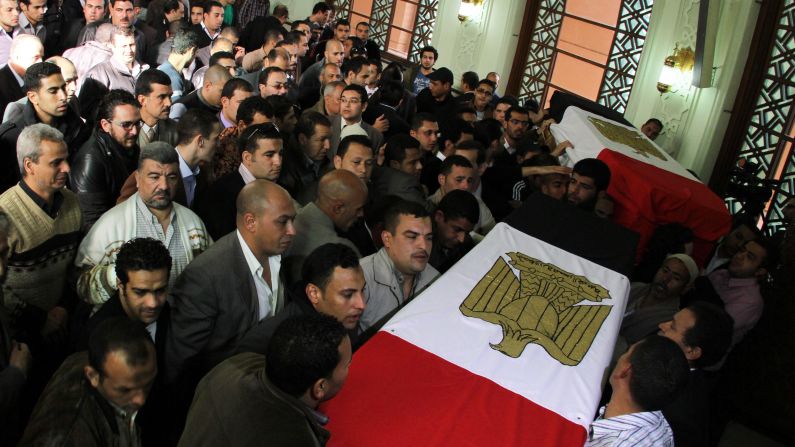

READ: 30 dead after Egyptians angry about riot verdicts try to storm prison

Exacerbating the political crisis is Egypt’s woeful economy, where the lifeblood of tourism is all but dead and the currency is devalued, analysts said.

Recent demonstrations in Port Said and nearby cities along the Suez Canal are symbolic because that region was among the first where the Mubarak regime lost control during the 2011 unrest leading to revolution, analysts said. The region has long felt distant from Cairo.

READ: Fear and loathing in Egypt: The fallout from Port Said

Demonstrators this week ignored the curfew Morsy imposed on the region following bloodshed on the second anniversary of the revolution last Friday. Protesters fed up with slow change clashed with authorities, leaving seven people dead.

Rage exploded again when a judge sentenced to death 21 residents of Port Said for their roles in a deadly soccer riot last year. At least 38 people were killed in the two days of violence after the verdict.

The defense minister denied reports that the army used live ammunition on the protesters, state-run media said.

“What struck me this time was the call for emergency law and emergency measures, and it was just ignored,” Cook said. “The people in Port Said were demonstrating and just thumbed their nose at the government.”

Protesters behind the Egyptian revolution now feel betrayed, particularly as the state security agency was changed in name only to homeland security, Stacher said. No one from Mubarak’s coercive security apparatus was sentenced for any violence during the revolutionary rallies, he said.

Protesters now just throw rocks at police during most encounters, he added.

“This all boils down to something very basic,” Stacher said. “The people demanded real change in Egypt but were lied to and their wishes were postponed and they were told they weren’t important.

“And the generals went around and created this exclusivist coalition (with Morsy’s government), which is what people were protesting against in the first place,” Stacher said.

In fact, protesters began calling Morsy “Morsilini,” a reference to the late Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini who was Adolf Hitler’s ally. That nickname arose after Morsy gave himself sweeping powers in November.

Morsy later canceled most of those powers following demonstrations. That turn of events hurt Morsy’s image because he was enjoying international attention for playing a constructive role in the recent, bloody conflict in Gaza between Hamas and Israeli forces, analysts said.

The stakes are high for a country strategically positioned in Middle Eastern politics and in world trade through the Suez Canal.

“I don’t think the international community can afford for (Egypt) to collapse economically … or politically,” Cook said.

The defense minister’s warning is “very important” because “it shows the military has been in consultation about this. That’s why I take it more seriously,” Cook added.

In the coming month, Egyptians will go to the polls to elect a lower house in Parliament. The election will be a bellwether on how Morsy’s Muslim Brotherhood now stands against the opposition coalition National Salvation Front, analysts said.

“They are smart people,” Stacher said of opposition leaders, “but the problem is that they don’t seem like they want to have a real democracy either.”

For now, the Egyptian military doesn’t appear to want to intervene and run the Egyptian government again as another president is selected.

“If the situation deteriorates further, the military might not have a choice and it might find a warm reception,” Cook wrote on his blog for the Council on Foreign Relations.

In a revolution, the first government typically doesn’t stay in power, as seen in the Russian and French revolutions, Coyle explained.

“Usually it gets replaced by more radical elements of society,” he said.

CNN’s Adam Makary contributed to this report from Port Said, Egypt